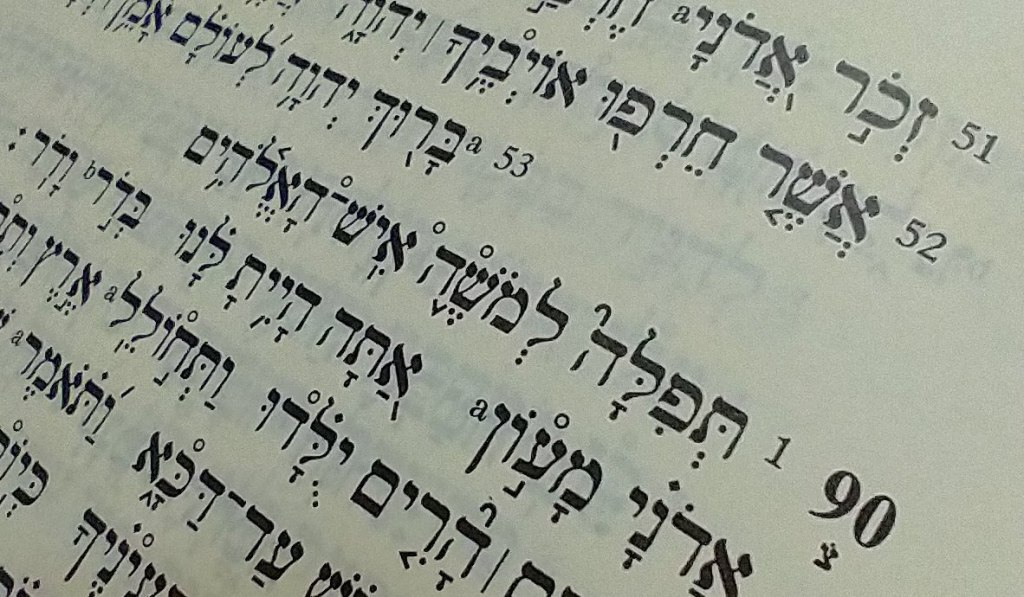

In my ongoing mini-project to write sermons on the songs in the Bible associated with Moses, I am now on Psalm 90, which is “a prayer of Moses, the man of God” (superscription in English Bibles [v. 1a MT]).

Before even dipping into commentaries, an attempt at translating the Hebrew told me that Psalm 90 is fraught with interpretive puzzles, not least of which is the opening attribution to Moses.

In what sense is it “a prayer of Moses, the man of God” (תפלה למשה איש האלהים)?

The ל (Lamed) of Authorship?

The preposition ל on Moses’s name (which I translated as “of” above) raises a few questions:

- Is it a prayer that Moses himself wrote or spoke aloud while another dictated it?

- Is it a prayer that someone else wrote in order to synthesize or summarize teaching or themes from Moses’s ministry or from the Pentateuch—such as Moses’s prayer to know God’s ways, to behold his face, and to see his glory (Exod 33.12–18)?

- Is it a prayer imitating Moses’s style?

In his translation-commentary on the Psalms, Robert Alter dismisses Moses’s authorship. The only reason that he gives is his negative evaluation of the argument of some scholars who connect Psalm 90 to the “Song of Moses” in Deuteronomy 32: the linguistic connections, Alter thinks, are “tenous” and “very few” (p. 317). But Alter’s point, if it can be sustained, gives a negative answer only to question #3 above; this poem does not necessarily imitate a Mosaic literary style that we see in the Pentateuch. But that assertion does not give a negative answer to question #1 above: the same person who first sang Deut 32.1–43 could also have composed Psalm 90—in a different style. A poet is under no obligation to maintain a particular style across genres, topics, and occasions. (My own style in a blog is different from what it is in a sermon or in an email to a colleague, etc.) There is nothing to say that YHWH’s didactic song given to Israel through Moses (cf. Deut 31.19–22) has to linguistically match Moses’s intercessory prayer for wisdom in the midst of hardship. Nor does Alter’s assertion give a negative answer to question #2 above: a student of Moses could have attributed the content of Psalm 90 to the teaching that he received from Moses; in this case, one would say that Psalm 90 reflects Moses’s teaching. In fact, Alter has so much trouble suppressing senses #1 and #2 that he translates תפלה למשה straightforwardly as “a prayer of Moses” (Ps 90.1; p. 317) though he elsewhere prefers to translate תפלה לדוד ambiguously as “a David prayer” (Ps 17.1; p. 48). The inconsistency is telling. Anyway, prayer is not a literary genre in Hebrew, and the ל is not attached to Moses’s name in order to show literary or generic connection.

Critical speculations against the text must bear the burden of proof.

I am critical of uncritical criticism that takes the text’s claims as false until proven true. Critical speculations against the text must bear the burden of proof. When Alter says, for example, that “Davidic [or Solomonic or Mosaic, etc.] authorship enshrined in Jewish and Christian tradition has no credible historical grounding” (p. xv), he is saying that the ancient text cannot be admitted as documentary evidence, that Psalm 90 cannot speak for itself, in a sense. Here Alter has not proved the point about actual authorship but has merely presupposed his own counterpoint, for neither is there “credible historical grounding” for denying the stated authorship.

Psalm 90 declares that it is authored by or at least derives in some way from Moses, and it is the critic who has to make the attempt at falsifying the text’s claim. Yet scholars who deny Moses’s authorship, J. Alec Motyer notes, “are notably short of impressive reasons for doing so” (NBC, p. 544)—as illustrated by Alter’s scant argumentation. Why can’t Psalm 90 have been first spoken and/or penned by Moses? I hear crickets.

For arguments in favor of the ל of authorship from the Hebrew Bible, Ugaritic sources, ancient Egyptian (Middle Dynasty) sources, Ben Sirach, Qumran sources, Josephus, and rabbinic sources, see Waltke, Old Testament Theology, pp. 872–73.

Putting Words in Moses’s Mouth?

There is still some question about whether the ל shows authorship (see quesiton #1 above) or some kind of loose thematic association (see question #2 above).

It can be the case that ל would mean something like “in association with” or “suitable to” (see GKC §119r; IBHS §11.2.10d; Joüon §133d; so Alter, Psalms, p. vx). Yet even if one were to grant that some ל attributions refer to a looser association, as Futato does in BTIOT, still “this is not to say that ‘of’ never refers to authorship” (p. 343). (I would further add that Futato’s argument from Proverbs for admitting this view of ל attributions is actually quite weak; see Waltke, Book of Proverbs: Chapters 1–15, pp. 31–36.) Yet we have plenty of “historical grounding” to say that the ל of the superscriptions was taken as a ל of authorship by the most ancient interpreters that we know: the writer of Chronicles, Ben Sira, the Qumran writers, Jesus and the New Testament writers, Josephus, and the rabbis (see Waltke and Houston, PACW, pp. 89–90). The “ל of authorship” is a clear part of Hebrew syntax (see GKC §129c; IBHS §11.2.10d,f; Joüon §130).

We also know that the so-called superscriptions containing ל of authorship are not late additions by interpreters. They are very old—old enough that Greek and Aramaic translators in the second-temple period didn’t know what they all meant (see Waltke and Houston, PACW, pp. 90–91).

It also seems that, in the case of Psalm 90, the so-called superscription makes a kind of “numerical perfection” (i.e., 140 words) when one includes the four words תפלה למשה איש האלהים (see van der Lugt, Cantos and Strophes, p. 17, n. 1, though note that van der Lugt’s analysis still treats the superscripts as secondary). In other words, the superscription in the Hebrew text may not be a “super”-scription properly speaking; it may be part of the poem itself. What if there was no anonymous proto-Psalm 90 lying around for a post-exilic editor to slap a label on? (In fact, we have no ancient versions of the Psalms without the superscripts that the Hebrew Masoretic Text has; see Waltke and Houston, PACW, p. 90.) What if there was no random scribe who read a proto-Psalm 90 and said, “This one reminds me of Moses”? What if whoever first composed Psalm 90 had Moses in mind at the beginning, such that the attribution is part of the whole?

Since the ל has been understood as referring to the author by people who knew ancient Hebrew fluently and since the announcement of the author seems to be part of the fabric of the poem—then have we any good reason for thinking that this not a prayer first prayed by Moses?

We can only come so far with historical argumentation.

We can only come so far with historical argumentation. We cannot prove on historical grounds that Moses was the original author. The historical evidence does not have that power, nor does it have the power falsify the claim that Moses was the author. We just have to read the text that is given to us—all 140 words of it.

Am I at fault for putting words in Moses’s mouth, then?

God’s Words in Moses’s Mouth

From a doctrinal perspective, I do hold that the words of Psalm 90 have been put in Moses’s mouth. But they were not put there by some anonymous scribe. They were put there by God (cf. Num 12.8; Deut 8.3; 18.18).

(You can read what I hold concerning the doctrine of inspiration, if you like.)

And at this point, we bring the whole discussion about Moses’s authorship into its proper place. Affirming Moses’s authorship provides and important perspective on Psalm 90, but it does not determine every aspect of the prayer’s meaning. Walke and Houston (PACW, p. 92) remind us of an important balance:

Most of the psalms, including those in which an author is identified, are written in abstract terms, not with reference to specific historical incidences, so that others could use them in their worship.

It is important for Psalm 90 to be interpreted in light of Moses’s authorship, yet it is important for Moses’s intention to be interpreted in light of the actual terms that he used. He composed a prayer on behalf of God’s people that can also be used for God’s people in perpetuity. His composition is not “his own” but belongs to God’s people as a gift, a deposit, an instrument for our sanctification and worship.

Vern Poythress (“Dispensing with Merely Human Meaning,” p. 486) sharpens the point even more:

The human writers, we say, wanted to serve God. So they wanted to express spiritual words with spiritual meanings. Consequently, they intended to communicate whatever God wanted to communicate through the Holy Spirit. On one level, this is true for any spiritual person; it is true for anyone who desires to honor God in word and deed. If a person loves God, he does not want his words or deeds to proceed in independence of God. He wants God to be working through them. He wants to be filled with God’s wisdom, and to express that wisdom in what he says. He wants God’s presence to fill his life and his words, in order that the words may honor God and bring a blessing to those addressed. He wants others to recognize that, in what he says, he is pointing beyond himself. He is not speaking from a platform of self-sufficiency, but in ways that honor God as the source of all wisdom and truth.

The conclusion that Poythress draws from that paragraph bears repeating:

Therefore, the intention of the prophet is to express the intention of God. Hence, focus on the intention of the human author, if taken with full seriousness and with attention to depth, leads to focus on God’s intention. The human author intends the divine intention. Thus, it is artificial—in the end false—to try to isolate a human author’s intention.

In the remainder of the article, Poythress clarifies that he in no way wants to ignore or push past the stated human author—in the case of Psalm 90, to push past Moses. Rather, one needs only to remember that Moses, explicitly identified as “the man of God” (v. 0 Eng.; v. 1 MT), has not spoken/written this prayer as fodder for historical speculation about himself. What we know about Moses in covenantal history—especially in Exodus–Deuteronomy, but in many other places besides (e.g., Matt 17.3)—enriches God’s communication to us through Psalm 90, and we lose that richness once we either discount the attribution or use it for historical speculation rather than as an aid to worship.

Now to work on how these four words contribute to the rest of Psalm 90.

Bibliography

- Alter, Robert. The Book of Psalms: A Translation and Commentary. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2007. Norton.

- Futato, Mark D. “Psalms.” Pages 341–55 in A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the Old Testament: The Gospel Promised. Edited by Miles V. Van Pelt. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2016. WTSBooks. BTIOT.

- Gesenius, Wilhelm. Hebrew Grammar. Edited by Emil Kautzsch. Translated by Arthur E. Cowley. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1910. Public Domain: Wikisource. GKC.

- Joüon, Paul. A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. Translated and revised by T. Muraoka. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Subsidia Biblica 27. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 2006. ABE Books. Joüon.

- Motyer, J. A. “Psalms.” Pages 484–582 in New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition, ed. D. A. Carson, R. T. France, J. A. Motyer, and G. J. Wenham. 4th ed. Downers Grove, IL: InterVasrity, 1994. WTSBooks. NBC.

- Poythess, Vern S. “Dispensing with Merely Human Meaning: Gains and Losses from Focusing on the Human Author, Illustrated by Zephaniah 1:2–3.” JETS 57.3 (2014): 481–99. Open Access: Frame-Poythress.org.

- van der Lugt, Pieter. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90–150 and Psalm 1. OtSt 63. Leiden: Brill, 2014. Brill.

- Waltke, Bruce K. The Book of Proverbs: Chapters 1–15. NICOT. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004. WTSBooks.

- Waltke, Bruce K. with Charles Yu. An Old Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Canonical, and Thematic Approach. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic, 2007. WTSBooks.

- Waltke, Bruce K., James M. Houston, with Erika Moore. The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008. WTSBooks. PACW.

- Waltke, Bruce K., and Michael O’Connor. An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990. WTSBooks. IBHS.

Leave a comment