It took a little longer than I expected, but thanks to a “dissertation boot camp” at CUA, I finally finished a draft on Hobbes’s use of the “chair of Moses” saying (Matt 23.2–3) in Leviathan (with brief mention of Behemoth).

Rather than go into 30-pages of nitty-gritty details, I offer one of my summary paragraphs here:

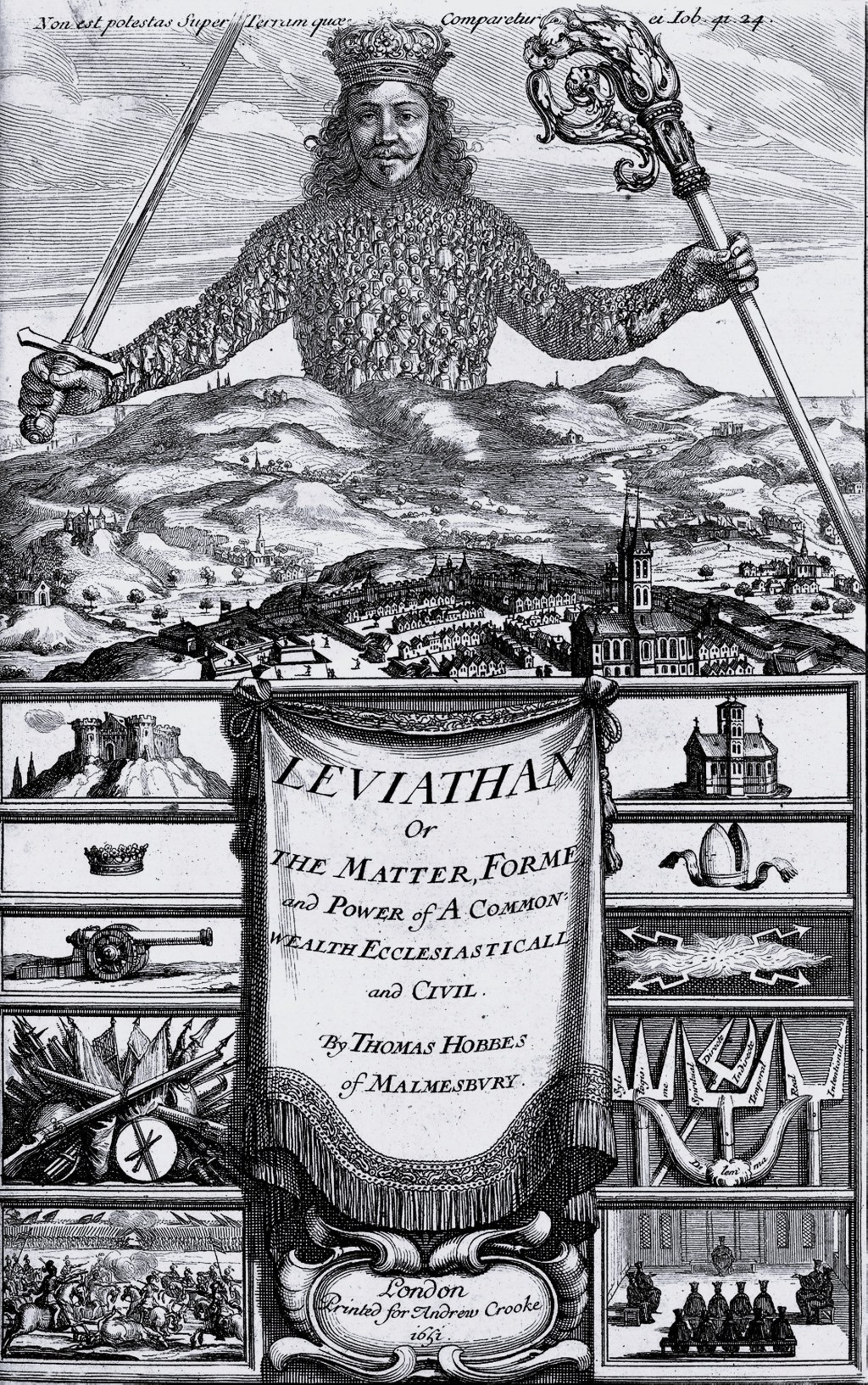

Hobbes interprets the chair of Moses consistently as a metonym for CIVIL SOVEREIGNTY, more specifically God’s sovereign authority administered through Moses in the first instantiation of the kingdom of God on earth. Christ’s purpose in the “chair of Moses” saying, then, is to encourage his disciples to fulfill the divine law in submitting to the laws promulgated by those with civil sovereignty. Hobbes is not here advocating the recovery or maintenance of the theocracy of Israel, which he holds to have ceased and to be awaiting restoration by Christ at his return. Rather, Hobbes sees Christ illustrating an “interregnum” principle: until the kingdom of God is re-established on earth, Christians of various commonwealths owe their civil sovereigns simple obedience in everything, including the interpretation of Scripture. For Hobbes, the “chair of Moses” saying—together with other verses like the household code of Col 3 (2.20.16, 3.42.2; H 106, 321) and the “render to Caesar” saying of Matt 22 (2.20.16, 3.41.4; H 106, 263)—cuts off any appeal to Christ’s sovereignty through the church or the Pope. And it makes no difference whether the civil sovereigns command what is right or wrong, or what their manner of life is; in all cases, for Hobbes, loyalty and obedience to one’s civil sovereign is necessary for those who are preparing themselves for Christ’s kingdom in the world to come.

Hobbes’s peculiar take on Israel’s history described in the OT (as if the special kingdom of God on earth began with Abraham and ended with the election of Saul!) and on the figure of Moses (whom Hobbes said was the first “person” of the Trinity!) sets him up for a singular use of the “chair of Moses” saying.

I have most of the raw material now for my chapters, and so I am going to turn my attention to the so-called methodology portion of the dissertation. I say “so-called” because I think that the word methodology is often misused and because one of the central arguments about Wirkungsgeschichte is that it is not a method and that it even undermines the claim that method is the way to truth. Anyway, I have more reading to do for this part of the dissertation.

Leave a comment